Echoes of Alienation: Rediscovering Our Place in the Natural World

There is a quiet irony in our modern search for nature. I recently took my daughters on a camping trip, hoping to escape the incessant hum of urban life and rediscover a piece of the wild that once defined our existence. We were not far from civilization, just a short drive from comfortable camping conditions. Within walking distance, there were modern bathrooms, running water, and electricity. But what struck me most was not the untouched beauty of the landscape, but my daughters' palpable discomfort. The rustling of leaves, the distant call of an owl, even the murmur of the wind through the trees seemed to unsettle them. Nature’s soundtrack, once the most familiar of lullabies, now felt intrusive, almost intimidating.

Nearby, a small farm bustled with the simple life of goats and chickens. When invited to milk a goat, only my youngest daughter, just six years old, stepped forward with the innocent curiosity that once defined our species. The others hesitated, shrinking back as if confronted by something wholly unnatural. The udder, an eternal symbol of sustenance and life, had become a source of discomfort and aversion. The natural world, which once shaped us, now feels like a forgotten language, one we no longer speak with ease or understanding.

This moment sharpened my awareness of a deep and growing rift, a chasm not only between us and the natural world, but within us. What was once as familiar as the sky and the earth now seems distant, even threatening. Our gradual journey from living with nature to alienation has felt almost imperceptible, like a 25-minute drive that transports us to an entirely different emotional galaxy. The distance is undeniable. We have grown wary of the very sights and sounds that once grounded us, highlighting a discomfort that is as much internal as it is external. We have grown accustomed to not seeing the stars and the lights of the sky. As we forget the sky, we lose a piece of ourselves. The natural, which shaped the contours of everyday life, has become something alien, an anxiety that lacks all proportion.

The Alienation Within: Estrangement from Self

But this alienation is not confined to forests and fields; it mirrors our inner lives. We are beings of the earth, yet our detachment from nature reflects a deeper disconnection from our bodies, from our essence. When we turn away from the natural, we also turn away from ourselves. Our bodies, once celebrated in their natural form, have become battlegrounds of discontent.

Modern society, in its relentless pursuit of control and perfection, has deepened this divide. The comforts of progress have distanced us from the rawness of being human. The imperfections that once marked the passage of life are now seen as defects to be corrected, not as truths to be embraced. In our search for an idealized version of ourselves, smooth, flawless, eternally youthful, we lose sight of the deeper beauty of imperfection. Our dissatisfaction grows, fed by the impossible standards we set against a world we no longer touch.

The Crisis of Modernity: The Loss of Natural Rhythm

Our carefully controlled environments, air conditioned homes, manicured lawns, endless rows of concrete, offer safety but sever us from the rhythms that once guided human life. Food, once grown with our own hands, now arrives in neat, sterile packages, detached from the soil that gave it life. The seasons change, yet our lives remain constant, bathed in the artificial light of screens and the predictable hum of technology. Our bodies, designed to move and stretch in response to nature’s demands, now sit idle, detached from the call of the earth. We have gained security but sacrificed the comfort of belonging.

This disconnection resonates beyond the physical. It shapes our consciousness, our emotions, our sense of belonging. Children, once natural explorers, now roam digital landscapes, disconnected from the tactile world that nourished generations before them. Try convincing a child to lift their eyes from a screen and look out at the horizon. The rise in mental and emotional struggles, anxiety, depression, a pervasive sense of emptiness, reflects not just a personal crisis but a cultural one. We are strangers in our own lives, swept up in the world we created, cut off from the earth that once held us together.

The Philosophical Roots of Alienation: From Rousseau to Marx

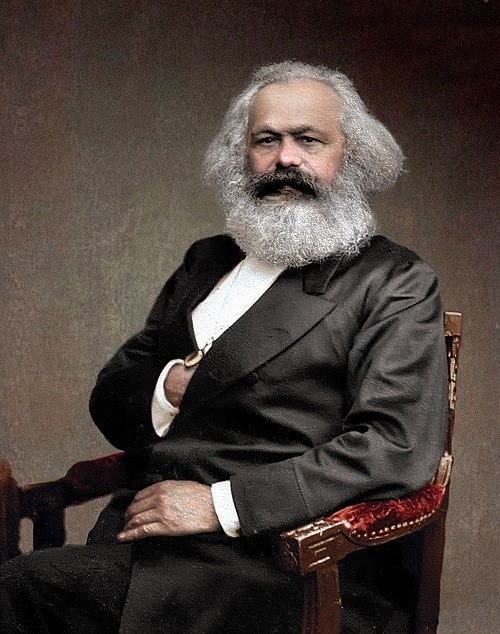

Our detachment from nature has deep philosophical roots that stretch back centuries. Rousseau lamented the loss of humanity’s “natural state,” a pure existence corrupted by the trappings of civilization. Marx, in turn, saw alienation as the inevitable consequence of a system that reduces human labor to a mere commodity. Both perspectives echo a profound sense of loss, a disconnection not just from nature but from ourselves.

These ideas, while rich in insight, often leave us mourning rather than mending. The task before us is not to wallow in the critique of modernity but to envision a path forward that bridges the gap between the world we have built and the one we have forgotten. It is a call to reimagine our place in the world, not as conquerors, but as stewards, reclaiming the wisdom of the past in the face of present challenges.

Rediscovering Ancient Wisdom: To Work It and To Keep It

The Torah offers us guiding light through its simple yet profound commandment: "to work it and to keep it"—לעבדה ולשמרה. These words capture a delicate balance between nurturing and preserving, control and humility. We are called to cultivate the land, to draw sustenance from its depths, but also to preserve its sanctity, to tread lightly, recognizing that it is not ours alone.

This command is more than ecological stewardship; it is a call to reconnect with a way of being that honors both our power and our limits. In a world obsessed with productivity, the simple act of being, observing without altering, nurturing without exploiting, feels almost revolutionary. To “work it” is not merely about extraction; it is about engaging in a relationship with the land that recognizes our shared fate. To “keep it” means remembering that we are not merely users of the earth, but its caretakers, bound to its rhythms and responsible for its future.

Tu Bishvat and Shabbat: Sowing the Seeds of Connection

The Jewish tradition of Tu Bishvat, the New Year for Trees, embodies this connection. Each year, Israeli children take to the fields, planting saplings that will grow alongside them. This ritual, rooted in centuries-old tradition, is more than a celebration of nature’s renewal; it is a deliberate act of connection. Over the past 120 years, the Jewish National Fund (KKL) has planted more than 260 million trees across Israel, weaving a green carpet that covers over 250,000 dunams. These efforts are not just about restoring land; they are about restoring a relationship.

This connection to the land is not utilitarian; it is existential. The trees planted on Tu Bishvat are symbols of life that lives not only on the land but also with it. The campaigns that have inspired generations to plant and care for trees are not just environmental; they are deeply spiritual. They remind us that we are not separate from the earth, but are nourished by it in every sense, physically, emotionally, spiritually.

Equally powerful is the tradition of Shabbat, a weekly pause that asks us to step back from the relentless pace of life. On Shabbat, we are called to disconnect from technology, from work, from the constant demands of modern existence. It is a day that invites us to be present, with our families, our communities, and the natural world. In the silence of Shabbat, we find a fleeting but profound return to a simpler state, where the world’s value is measured not by utility but by quiet presence.

Shabbat is more than rest; it is resistance. It is a deliberate refusal to be imprisoned by the world’s endless appetite for more. It teaches us to value not what we produce but who we are, to be together, and to find joy not in acquisition but in shared moments. It is a celebration of our participation in a grand and enduring symphony.

Reclaiming Our Connection: Practical Steps Toward Renewal

To rebuild our connection with nature, we can start with simple and deliberate actions. Planting a garden, taking a walk, or sitting in quiet contemplation can reconnect us to the natural world and to ourselves. Schools and communities can prioritize outdoor education, teaching children not just to observe but to engage with the environment. City planners can design cities that invite nature in, creating spaces where green is not an afterthought but a central and vivid part of the urban landscape.

We need not abandon the comforts of modernity, but we should blend them with a renewed respect for the land and, by extension, for ourselves. It is not about turning back time, but about moving forward with an awareness that honors our roots. If we reimagine our relationship with nature, we can begin to mend the rift that separates us from the land and from each other.

Our alienation from nature is, in many ways, a reflection of a broader disconnection that pervades our relationships, our work, and our sense of self. Yet within this alienation lies the potential for rediscovery. If we can learn to balance the benefits of progress with a reverence for the natural world, we may find a way to live that is both prosperous and profound.

By paving a new path, one that leads us back to ourselves, we can find value not in what is profitable or efficient, but in what is enduring. The rustling leaves, the flowing streams, the quiet moments of presence, they are not just remnants of a lost world; they are echoes of a truth we are called to remember. A truth that tells us that we are not merely inhabitants of the earth, but part of its living, breathing soul.

The Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) chronicles the history of a people living in close relationship with God and His creation. Today we study the Tanakh for the purpose of analysis, rather than using it as a guide to what matters in life.

Even so, the post-Tanakh Jewish tradition offers us a path to mindfulness: the recitation of blessings that sanctify the most mundane acts.